What Drew Me to Son Doong

More than a year ago, I booked a tour to Son Doong Cave after watching a short video of what’s now known as the largest cave in the world. The images stayed with me, not just for the sheer scale, but for the sense of another world hidden below the surface. I didn’t know it at the time, but this journey would uncover much more than limestone formations. It would reveal an entire community’s transformation.

By chance, I arrived in Vietnam during Reunification Day, April 30th, 2025, which is fifty years after the Vietnam War ended. A fitting backdrop to revisit a region long shaped by conflict, now rewriting its story through conservation and care.

From War Zone to Wilderness Gateway

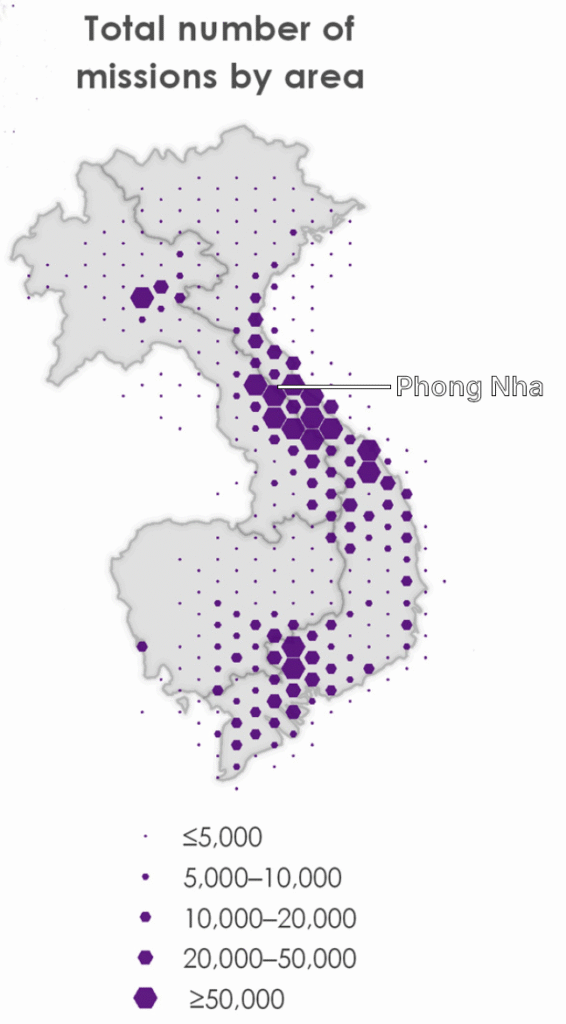

Son Doong is located in Phong Nha, a region that, long before it became synonymous with adventure tourism, was a frontline of survival. During the Vietnam War, this region endured relentless bombing as part of a broader campaign to disrupt North Vietnamese supply lines along the Ho Chi Minh Trail. Phong Nha’s strategic position, with its dense jungle, mountains, and vast cave networks, made it a haven for troops and a target for U.S. forces.

During the war, around 7 million tons of bombs were dropped on Vietnam. At the height of the conflict, Phong Nha was one of the most heavily impacted regions and experienced up to five bombings per day.

Even today, fifty years later, unexploded bombs remain buried beneath the soil, a silent danger woven into the landscape. Organizations like MAG (Mines Advisory Group) continue the work of clearing these remnants, often in close collaboration with local communities. Yet despite their efforts, the harsh reality persists: some locals, driven by economic hardship, still risk their lives scavenging these deadly munitions to earn a living.

“If they are caught with the bomb, they will go to jail for seven years. But if they can sell it for scrap metal, they will put food on the table for many weeks.”

The discovery of Son Doong in 2009 and its opening to limited tourism in 2013 marked a turning point. What was once a region shaped by conflict and obscured by history has transformed into a destination of awe and exploration. Today, the same jungle trails once walked in the shadow of war are retraced by trekkers in search of wonder, not survival.

Phong Nha: Vietnam’s Underground Giant

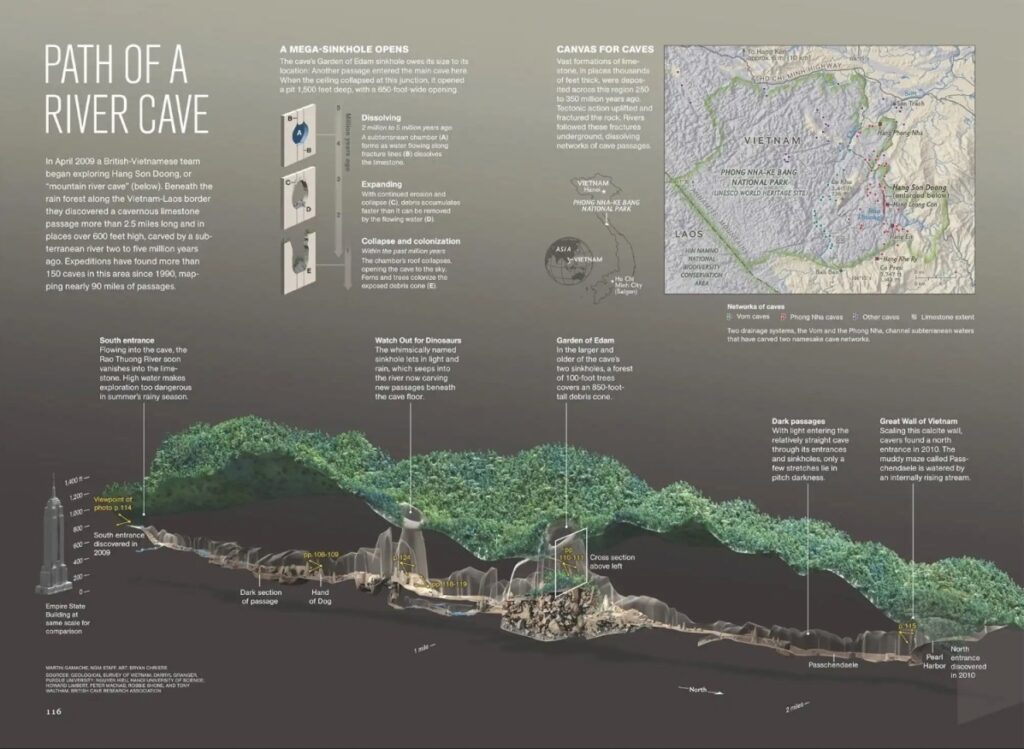

The Phong Nha-Ke Bang National Park is a UNESCO World Heritage Site that hides hundreds of caves. The park encompasses over 400 caves, with estimates suggesting that this represents only about 30% of the total cave systems present. This means that a significant portion of Phong Nha’s underground wonders remains unexplored, offering immense potential for future discoveries.

The highlights:

- Son Doong Cave: The largest in the world by volume.

- Hang En: The third-largest globally.

- Tu Lan and Hang Tien: Famous for underground rivers and Jurassic-era formations.

Many of these caves were unknown to science until the early 2000s. While locals had known of these caves for generations, it wasn’t until expeditions by the British Cave Research Association, led by Howard Limbert, that systematic exploration and mapping began. These efforts unveiled the vastness and complexity of the region’s subterranean networks, including the discovery of Son Doong Cave.

Son Doon is so vast that it contains its own jungle, clouds, and weather system. At approximately 9 kilometers (5.6 miles) long and at some points 200 meters high and 150 meters wide, large enough to fit a 40-story skyscraper or a Boeing 747. Its dolines (collapsed ceilings) let in shafts of daylight, allowing trees, moss, and even a unique ecosystem to thrive below ground.

It’s not just a cave — it’s a lost world.

Tourism as a Lifeline

Oxalis Adventure, the only company authorised to run Son Doong tours, follows a strict “one cave, one company” model to prevent over-tourism. It employs over 600 staff, 450 of whom are local. Many are the same people who once survived off war remnants or illegal forestry, now transformed into porters, safety team members, and environmental monitors.

In the wider community:

- The village of Tu Lan now has floating homes that rise with the annual floods.

- Solar panels power homestays and kitchens.

- Homestays have grown from 40 in 2010 to 400+ today, offering locals a reliable income while travellers experience authentic rural life.

Conservation That Pays

Vietnam backs its conservation commitments with real funding. The government offers up to 20 billion VND (approx. $800,000 USD) to communities that meet strict sustainability targets, like:

- Avoiding illegal logging or wildlife harm

- Maintaining the cave structures’ natural integrity

- Achieving carbon neutrality through practices like solar energy and zero-waste trekking

Inspectors visit multiple times a year. If a zone meets the criteria, it receives the payout, which supports everything from education to clean water infrastructure.

Even the expedition camps now operate with 100% solar power and rainwater systems. The entire tourism model is built around low impact and long-term gain.

A Jungle That Sustains

Once, this jungle threatened life. Now, it sustains it. The same forests that hid families during war now provide jobs, dignity, and stability. The same caves that shielded lives now support livelihoods.

Son Doong may have started as a viral adventure. But its real story is slower, deeper, and far more powerful. Proof that thoughtful tourism can rewrite the future of a region, not just for visitors, but for the communities that call it home.

Experience It Yourself

This journey through Son Doong wasn’t just about the scale of the cave or the beauty of the landscape. It was about the people, the stories, and the powerful reminder that adventure can be a force for good. I’m glad to be supporting a community-focused adventure tourism company. One that gives back to locals and inspires people around the world, including me, to tread more lightly on this planet.

Learn more or book the tour: Oxalis Adventure